It's pretty impressive to see how many different ways nonfiction authors can present the very same subject matter or the very same people in their books. To get the gist, today I thought it might be fun to compare some examples of books on the same topic--mostly (but not entirely) by our own INK authors and illustrators. I'll be brief, I promise.

So how about starting with our foremost founding father, George Washington himself. Each of these 3 authors has come up with entirely different hooks to pique your interest, so a young audience could get a pretty well-rounded view of our guy by checking out these true tales.

First up is The Crossing: How George Washington Saved the American Revolution by Jim Murphy. His hook is to focus on Washington's growth as a leader, obviously leading up to the famous crossing of the Delaware on Christmas in 1776. He's used some very interesting artwork from the period to enhance the tale.

Next comes an entirely different take on George from Marfe Ferguson Delano. Her book, Master George's People, tells the story of George's slaves at Mount Vernon, and she has collaborated with a photographer who shot pictures of reenactors on the scene.

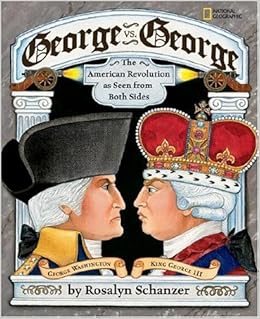

And this one is (ahem) my version. George vs. George: The American Revolution as Seen from Both Sides shows how there are two sides to every story. I got to meet George Washington and King George III and paint their pictures myself.

OK, on to the second set. In one way or another, the next 3 books are all based upon Charles Darwin and his Theory of Evolution. Let's start with Steve Jenkins' handsome book Life on Earth: The Story of Evolution. With a nod to Darwin, Steve has created a series of stunning collages along with fairly minimal text in order to focus on the history of all the plants and animals on the planet.

And here's yet another nod to Deb Heiligman for her celebrated true tale of romance between two folks with opposite views of the world. Despite Emma's firm belief in the Bible's version of life on earth, she and Charles enjoy a warm and loving marriage.

Mine again. What Darwin Saw: The Journey that Changed the World, tells about Darwin's great adventures as a young guy while traveling around the world. We're on board In this colorful graphic novel as he picks up the clues that lead to his Theory of Evolution and then does the experiments that prove it.

And here's series number 3. Apparently these authors and illustrators were hard at work at the very same time on three very different picture books about the very same person; her name is Wangari Maathai, and she won the Nobel Peace Prize for bringing Kenya's trees back to life after most of them had disappeared.

The artwork in all three books is outstanding, and each version is truly unique. The writing styles vary enormously too. I strongly recommend that you look at them side by side to prove that there's more than one way to skin a cat.

Planting the Trees of Kenya was written and illustrated by Claire A. Nivola.

Wangari's Trees of Peace was written and illustrated by Jeanette Winter.

And Mama Miti was written by Donna Jo Napoli and illustrated by Kadir Nelson.

I'd bet anything that these folks didn't know they were creating books about the same person until all 3 versions were finally published....writing and illustrating books is a solo occupation if there ever was one.

OK, that's it--though we could easily go on and on. Here's hoping that if any kids examine a whole series of books on the same topic written and illustrated in such different ways, they can come up with some unique new versions of their own....and have some fun at the same time.