When I think of thankfulness and books, I think of author Byrd Baylor. She writes both fiction and nonfiction. But all of her books are full of truth—resonant truth that bubbles up out of her clear prose. Her books, such as THE WAY TO START A DAY have been around for a while. But read them or re-read them and I think you'll find they hit home. They give thanks, for life and nature, at an elemental level.

THE TABLE WHERE RICH PEOPLE SIT is a perfect book for this economy and this particular November day. THE WAY TO START A DAY is a celebration of life and worth savoring. EVERYBODY NEEDS A ROCK is one of my favorites as a lover of science and rocks. I know the deep, intimate process of finding THAT rock. It is an essential way to connect in a sensory way with Earth.

For educators, Baylor's books are a terrific introduction to nonfiction voice. She is a master of both intimate storytelling and exposition. Her books show the power of unhurried prose. She doesn't throw something in your face and demand you love it. She shares. She calls on touchable, tastable details that bring big concepts to small fingers and hearts.

I call on her publisher to re-issue a Byrd Baylor collection. I'll buy it and tell everyone I meet about it. Her voice, as a nonfiction writer, is something special. I didn't come across Baylor's work until I'd been writing and publishing picture books for quite a while. But when I found them . . . ah. Her books are the kind that make me hug them to my chest and just sigh. After reading, I look around with new eyes. Wherever you are, Byrd, thanks for your work.

Happy Thanksgiving, all!

April Pulley Sayre

http://www.aprilsayre.com/

Blog Posts and Lists

Thursday, November 27, 2008

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

My Fifteen Minutes

Andy Warhol’s allotment of fame came in two installments for me this fall. My latest book, Jeannette Rankin: Political Pioneer has gotten nice attention this year: several notable lists, two awards, and one finalist. Who knew when I began writing it several years ago that this would be the year of the political woman? Not I.

The Children’s Literature Council of Southern California’s award ceremony was preceded by a scrumptious brunch at the Bowers Museum of Art in Santa Ana. Masks and sculptures from Oceania lined the room; a wall of window looked out onto an Asian-themed garden. Then we processed to an auditorium where authors and illustrators of various genres gave five-minute award acceptance speeches, mine for an Inspiring Work of Nonfiction.

As a member of this congenial group of librarians and authors for the last decade or so, I’d harbored a secret wish to win their award – and now I had done it. I’ve been a public speaker for decades. I’m at ease speaking to kids in schools, college students in classrooms, the general public in all sorts of venues. But this was different. I surprised myself by getting choked up as I spoke to my peers who were honoring me and my work.

Five minutes and it was over.

Two weeks later, the Simon Wiesenthal Center/Museum of Tolerance gave me the first Once Upon A World Award for young adult literature. (Their picture book award is thirteen years old, won this year by Ellie Crowe for Surfer of the Century: The Life of Duke Kahanamoku.) This was an afternoon event, open to the public and filled with winning-book-related events. Children made campaign buttons in an art activity room. (Jeannette Rankin was our first Congresswoman.) A storyteller narrated some of Rankin’s life in another room filled with beanbag chairs.

At the ceremony itself I did a ten-minute monologue as Rankin, wearing period hats. Then came the award and photo-op (no choking-up this time,) followed by a reception [see recipe below] and signing, then a dinner party at the elegant home of the award’s sponsor. And my book now wears a gold seal.

At the ceremony itself I did a ten-minute monologue as Rankin, wearing period hats. Then came the award and photo-op (no choking-up this time,) followed by a reception [see recipe below] and signing, then a dinner party at the elegant home of the award’s sponsor. And my book now wears a gold seal.5 minutes + 10 minutes = my 15 minutes

Between those two events, I traveled to Missoula (Rankin’s hometown) for the Montana Festival of the Book, a fun-filled two-day event featuring talks, panel discussions, readings, and signings by 140 authors, mostly Montanans who knew each other. Film screenings, art exhibits, and a poetry slam provided entertainment in the evenings. I spoke on two panels with biographers, novelists, and librarians – and paid a school visit to students who, unlike most kids, had already heard of Rankin, a Montana heroine. All that and gorgeous autumn weather -- golden glowing cottonwoods and larch trees -- made for a memorable weekend. (Hanging out with my son, who lives there, was an added bonus.)

I love talking about books. I love being surrounded by other writers and I was happy to be just one of 140 in Montana. But every once in a while I do like that dollop of icing on the cake – see below – when I and my books are the center of attention.

Recipe for Literary Icing

The folks at the Museum of Tolerance created a Jeannette Rankin edible book cover cake! Here’s how they told me you do it:

1) Scan the book cover.

2) Print it onto a sheet of edible rice paper (with edible food coloring.)

3) Lay carefully over a large sheet cake.

4) Eat!

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Texting

True conversation overheard at dinner one night in suburban NYC.

Teen H.S. student: “I have to go finish my homework. I still have twenty pages to read in my history textbook. It’s the most boring piece of crap ever.”

Teen’s father, graduate of top academic high school in NYC: “Oh, you must be using the same textbooks we did.”

Teen’s younger brother: “Well, my history textbook still calls Russia the USSR.”

(names have been withheld to protect blogger from family's wrath)

What's with the boring, outdated nonfiction?

If we hope to successfully analyze how we can make nonfiction more appealing, our first step needs to be acknowledging what nonfiction kids are actually reading. Most school age children read nonfiction every night. It's true. They do their homework(usually) and they read their textbooks. The sad reality is this is often their only form of nonfiction reading and, it can be argued, a primary reason they don’t pursue nonfiction further.

As the above conversation references, we need to seriously consider textbooks as well as school and library editions-- forms of nonfiction that dominate the school environment --because this is how children are exposed to nonfiction. It starts early in kindergarten and first grade, where the classrooms offer less expensive, paperback library nonfiction. Then it’s on to textbooks which have been known to actually cause a child to loose interest in a subject. No matter how creative nonfiction writers get, the truth is that kids first and predominant exposure to nonfiction has not had any significant improvements in the last thirty years. Or is it longer?

I read an interesting article recently about a watchdog organization devoted to trying to help journalists approach their topics from a position of knowledge and understanding. Its goal is to find ways for journalist to become more educated on the subject matters they cover so that their articles have the depth and understanding of someone who is actually involved in education, the environment, politics or whatever subject they are writing about.

Perhaps children’s publishing could benefit from a similar approach. There is currently a lot of “we only do literary fiction” or “we publish solely for the library market” kind of isolating talk and behavior. Kids don’t break down their reading habits in this way; it doesn’t serve them well that the professionals do. If nonfiction is going to really push through the old barriers, we have to look at the bigger picture. If we understand what they read, required and otherwise, from an early age then perhaps we can understanding how to keep them interested as they grow older.

Kids today are still going to spend a lot of time texting and instant messaging. But it still might be possible to engage them with a new, improved old school kind of text.

Teen H.S. student: “I have to go finish my homework. I still have twenty pages to read in my history textbook. It’s the most boring piece of crap ever.”

Teen’s father, graduate of top academic high school in NYC: “Oh, you must be using the same textbooks we did.”

Teen’s younger brother: “Well, my history textbook still calls Russia the USSR.”

(names have been withheld to protect blogger from family's wrath)

What's with the boring, outdated nonfiction?

If we hope to successfully analyze how we can make nonfiction more appealing, our first step needs to be acknowledging what nonfiction kids are actually reading. Most school age children read nonfiction every night. It's true. They do their homework(usually) and they read their textbooks. The sad reality is this is often their only form of nonfiction reading and, it can be argued, a primary reason they don’t pursue nonfiction further.

As the above conversation references, we need to seriously consider textbooks as well as school and library editions-- forms of nonfiction that dominate the school environment --because this is how children are exposed to nonfiction. It starts early in kindergarten and first grade, where the classrooms offer less expensive, paperback library nonfiction. Then it’s on to textbooks which have been known to actually cause a child to loose interest in a subject. No matter how creative nonfiction writers get, the truth is that kids first and predominant exposure to nonfiction has not had any significant improvements in the last thirty years. Or is it longer?

I read an interesting article recently about a watchdog organization devoted to trying to help journalists approach their topics from a position of knowledge and understanding. Its goal is to find ways for journalist to become more educated on the subject matters they cover so that their articles have the depth and understanding of someone who is actually involved in education, the environment, politics or whatever subject they are writing about.

Perhaps children’s publishing could benefit from a similar approach. There is currently a lot of “we only do literary fiction” or “we publish solely for the library market” kind of isolating talk and behavior. Kids don’t break down their reading habits in this way; it doesn’t serve them well that the professionals do. If nonfiction is going to really push through the old barriers, we have to look at the bigger picture. If we understand what they read, required and otherwise, from an early age then perhaps we can understanding how to keep them interested as they grow older.

Kids today are still going to spend a lot of time texting and instant messaging. But it still might be possible to engage them with a new, improved old school kind of text.

Monday, November 24, 2008

It's "Math-Lit" But Is It Good Lit?

I am just back from San Antonio, where I spoke at NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English). An annual appearance at NCTM (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics) has been on my agenda since 1996 but this was my first NCTE. I started thinking about similarities and differences between the two organizations in how they encourage teachers to use literature, and I mostly came up with similarities. And then I remembered a book on my shelf at home that makes that point exactly, focusing on mathematical literature. Appropriately, the book is published jointly by NCTM and NCTE. If I could put just one resource in the hands of a teacher wanting to mine the many treasures of “math-lit” as a teaching tool for both mathematics and language arts, this would be the book.

+cover.jpg)

1. Mathematical integrity Stories and literature have enormous value when they inspire children to apply mathematical ideas to the world around them, but for that to happen, the math in a book should be not only accurate, but should be presented in a context that is believable, not forced; it should be presented in an accessible way; and it should “promote healthy mathematical attitudes and dispositions.”

The Whitins give several examples, including Ann Whitehead Nagda’s Tiger Math: Learning to Graph from a Baby Tiger, which provides both an exciting non-fiction narrative with photographs and statistical data from the true, suspenseful story of a motherless tiger cub being raised at the Denver Zoo. Data (such as weight gain over time) is expressed in a variety of useful graphs. It’s an engaging book that connects math to the real world in a way children find spellbinding — and educators find supportive of the standards they are trying to teach.

3. An aesthetic dimension “Good books appeal to the emotions and senses of the reader, provide a fresh perspective, and free the imagination.” Here the Whitins look at how well the written language is crafted, along with the quality of the visuals and whether the book actually inspires a greater appreciation of the wonders of the world (including the human world). To earn our respect, the words and visuals of a work of mathematical literature must be just as compelling as those of any other literary genre. Claiming "It's just a math book!" doesn't cut it.

4. Racial, cultural and gender inclusiveness. My first reaction to this criterion was a bit dismissive. “Doesn’t that apply to all books?” I asked. Of course it does, but we should be especially careful not to let the

+cover.jpg)

New Visions for Linking Literature and Mathematics by David J. Whitin and Phyllis Whitin is more than a resource book about using math-related literature in the classroom. It does indeed illustrate a myriad

ways that teachers can use a wide range of quality b

ooks to support both math and literacy. But note the word “quality.” In addition to providing examples (plenty!) and illustrating how teachers have used them (impressive!), it tells you how to judge mathematical literature. That’s where New Visions differs from any other resource book I’ve seen. “Many (math-related books) seem more like workbooks than stories,” write the Whitins and I agree wholeheartedly. “Some give detailed prescriptions for reading, much like a teaching manual for a basal reader, while others mask doses of ‘skills’ with comical illustrations or popular food products…” Bottom line: not all math lit is created equal, and New Visions shows you how to evaluate. It even shows why some books just don’t make the grade, and it does name names. Harsh! But someone had to do it.

The Whitins put forth four criteria as a guide for judging mathematical literature as worthy. They then select one book as exemplary, showing how it makes the grade in all four areas. More on that later. Here are their criteria with an example of a book that stands out in each category.

1. Mathematical integrity Stories and literature have enormous value when they inspire children to apply mathematical ideas to the world around them, but for that to happen, the math in a book should be not only accurate, but should be presented in a context that is believable, not forced; it should be presented in an accessible way; and it should “promote healthy mathematical attitudes and dispositions.”

The Whitins give several examples, including Ann Whitehead Nagda’s Tiger Math: Learning to Graph from a Baby Tiger, which provides both an exciting non-fiction narrative with photographs and statistical data from the true, suspenseful story of a motherless tiger cub being raised at the Denver Zoo. Data (such as weight gain over time) is expressed in a variety of useful graphs. It’s an engaging book that connects math to the real world in a way children find spellbinding — and educators find supportive of the standards they are trying to teach.

2. Potential for Varied Response. Children’s books should not be worksheets. Instead of being didactic, they should encourage children to think mathematically and invite them to “investigate, discuss, and extend… (and to) engage in research, problem posing and problem solving.” Readers are not directed. They are invited.

Readers of the charming Grandpa’s Quilt by Betsy Franco, are easily tempted to find their own solutions the problem that faces the book’s characters. The 6-square by 6-square quilt does not cover their grandfather’s feet so they must rearrange its dimensions. Children are likely to explore factors of 36 and to get a feel for the relationship between perimeter and area. And the mathematical “invitations” go on from there.

3. An aesthetic dimension “Good books appeal to the emotions and senses of the reader, provide a fresh perspective, and free the imagination.” Here the Whitins look at how well the written language is crafted, along with the quality of the visuals and whether the book actually inspires a greater appreciation of the wonders of the world (including the human world). To earn our respect, the words and visuals of a work of mathematical literature must be just as compelling as those of any other literary genre. Claiming "It's just a math book!" doesn't cut it.

In their unique counting book, Spots: Counting Creatures from Sky to Sea, author Carolyn Lesser and illustrator Laura Regan use vivid, evocative language and stunning paintings to inspire awe and appreciation of nature — as well as the mathematics that is so often useful in describing and explaining the natural world.

4. Racial, cultural and gender inclusiveness. My first reaction to this criterion was a bit dismissive. “Doesn’t that apply to all books?” I asked. Of course it does, but we should be especially careful not to let the

mathematical component of literature that perpetuates stereotypes blind us to an unfortunate sub-text. There is a huge push now to attract women and members of ethnic minorities to careers in mathematics, science and engineering, and children’s books can help promot

e equity. There is more to it than counting boys vs. girls or white children vs. black or brown children in the illustrations. As one of several fascinating examples, the Whitins sing the praises of The History of Counting by eminent archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat, a non-fiction picture book that celebrates the contributions

of many cultures over many centuries in developing diverse number systems.

New Visions for Linking Literature and Mathematics goes on to provide myriad examples of books for a wide range of ages, strategies for using them to teach math, and an outstanding annotated bibliography called “Best Books for Exploring.”

Now about that exemplary book the Whitins chose to feature in the opening chapter. I held off identifying it until now for fear of seeming self-serving, but in the interest of full-disclosure, I should say that it’s my book If You Hopped Like a Frog. I’ve written about it in earlier posts so I won’t summarize it now and it would really feel way too “me”-focused to list the ways the authors of New Visions found that it met their four criteria. Instead, I’ll close with a passage from an article published in Horn Book in 1987, quoted by the Whitins. I can think of no better summary of their feelings and mine:

“You can almost divide the nonfiction [that children] read into two categories: nonfiction that stuffs in facts, as if children were vases to be filled, and nonfiction that ignites the imagination, as if children were indeed fires to be lit.” (Jo Carr, “Filling Vases, Lighting Fires” Horn Book 63, November/December 1987.)

New Visions for Linking Literature and Mathematics goes on to provide myriad examples of books for a wide range of ages, strategies for using them to teach math, and an outstanding annotated bibliography called “Best Books for Exploring.”

Now about that exemplary book the Whitins chose to feature in the opening chapter. I held off identifying it until now for fear of seeming self-serving, but in the interest of full-disclosure, I should say that it’s my book If You Hopped Like a Frog. I’ve written about it in earlier posts so I won’t summarize it now and it would really feel way too “me”-focused to list the ways the authors of New Visions found that it met their four criteria. Instead, I’ll close with a passage from an article published in Horn Book in 1987, quoted by the Whitins. I can think of no better summary of their feelings and mine:

“You can almost divide the nonfiction [that children] read into two categories: nonfiction that stuffs in facts, as if children were vases to be filled, and nonfiction that ignites the imagination, as if children were indeed fires to be lit.” (Jo Carr, “Filling Vases, Lighting Fires” Horn Book 63, November/December 1987.)

Friday, November 21, 2008

Photography and Nonfiction Kids' Books

Today, I realized with surprise that only a couple of posts have dealt with photography in nonfiction children’s books. Especially for books beyond grades 3 or 4, photography plays a huge role in both the effectiveness and success of a book. How does an author get the photos he or she needs?

In some cases, publishers do the work. With my “American Heroes” biographies and my book Pocket Babies, for instance, I have been fortunate to work with publishers that do a wonderful job at photo research. Taking my own photos, however, has been pivotal to the some of my most successful books. And yet, I do not consider myself a professional photographer. How does that work?

Well, the answer is that back in 1994, I bought a camera system that is smarter than I am. Before that time, I tried to take professional-grade photos using a manual 35-mm Olympus system. Just couldn’t do it. Even though I spent a great deal of time trying, the photos always came out slightly out-of-focus or with the wrong metering. Today’s cameras are so good, though, that they solve most of these issues. Still, that doesn’t mean that I’m home-free.

Most books require a few specialized shots that someone like myself just cannot get. So a key for me is recognizing the kinds of photos I can take myself. I limit myself, for example, to subjects that are close and holding still. Fortunately, that includes 90% of most photos I ever need for a book, from plants and landscapes to insects and people. Another big key is using a tripod. Even on a well-lit, still day, a tripod is almost essential for getting that crispness that I must have to make a picture publishable.

For the other photos I need, I just plan on obtaining those elsewhere. People I am interviewing for my books often have these available. For my new book Science Warriors: The Battle Against Invasive Species, I was able to obtain some key close-up—and gruesome—photos of flies emerging from an ant’s head from a scientist who works with this system. For my book The Prairie Builders, the refuge I featured had a number of historical photos in their collection I could use.

While part of me dreads getting photos together for a book, a larger part really enjoys the process. Documenting a research trip with photos actually helps me a lot with the writing process. And you just can’t beat being right in a place taking the pictures you need. BTW, I use a Canon system with a macro lens, a wide-angle lens, and a zoom 50-300 mm. And don’t faint now—I still shoot film! That will surely change with the next big photo book, but for now, it’s all worked remarkably well—and enriched my entire writing process.

In some cases, publishers do the work. With my “American Heroes” biographies and my book Pocket Babies, for instance, I have been fortunate to work with publishers that do a wonderful job at photo research. Taking my own photos, however, has been pivotal to the some of my most successful books. And yet, I do not consider myself a professional photographer. How does that work?

Well, the answer is that back in 1994, I bought a camera system that is smarter than I am. Before that time, I tried to take professional-grade photos using a manual 35-mm Olympus system. Just couldn’t do it. Even though I spent a great deal of time trying, the photos always came out slightly out-of-focus or with the wrong metering. Today’s cameras are so good, though, that they solve most of these issues. Still, that doesn’t mean that I’m home-free.

Most books require a few specialized shots that someone like myself just cannot get. So a key for me is recognizing the kinds of photos I can take myself. I limit myself, for example, to subjects that are close and holding still. Fortunately, that includes 90% of most photos I ever need for a book, from plants and landscapes to insects and people. Another big key is using a tripod. Even on a well-lit, still day, a tripod is almost essential for getting that crispness that I must have to make a picture publishable.

For the other photos I need, I just plan on obtaining those elsewhere. People I am interviewing for my books often have these available. For my new book Science Warriors: The Battle Against Invasive Species, I was able to obtain some key close-up—and gruesome—photos of flies emerging from an ant’s head from a scientist who works with this system. For my book The Prairie Builders, the refuge I featured had a number of historical photos in their collection I could use.

While part of me dreads getting photos together for a book, a larger part really enjoys the process. Documenting a research trip with photos actually helps me a lot with the writing process. And you just can’t beat being right in a place taking the pictures you need. BTW, I use a Canon system with a macro lens, a wide-angle lens, and a zoom 50-300 mm. And don’t faint now—I still shoot film! That will surely change with the next big photo book, but for now, it’s all worked remarkably well—and enriched my entire writing process.

Thursday, November 20, 2008

Passionate Nonfiction and Staying True to Your Readers

I tried to post this before leaving for San Antonio this morning for the NCTE/ALAN conference, but it didn’t work. I’m hoping I can tap into the wireless during my next layover and send this off to cyberland from Newark. If you’re reading this, I have succeeded.

The topic our NCTE (National Council for Teachers of English) panel will be discussing is how we, as nonfiction writers, remain a reliable source of information while sharing our passion and point of view on a topic with young readers. It’s a very good question and one that I, like my fellow panelists—Marc Aronson, Elizabeth Partridge, and Tonya Bolden—and other nonfiction writers spend a great deal of time thinking about and incorporating when we transfer our thoughts to the page.

There are many factors that come into play, especially when writing for an audience that is older than the picture book crowd. When I delve into a topic I try to learn as much as humanly possible on a subject. This means that I sometimes uncover issues that not be entirely positive or may be difficult to address with kids. But it certainly doesn’t mean that I avoid those issues. For example, while researching Ella Fitzgerald for my Up Close: Ella Fitzgerald book, I discovered that there were many half-truths or misperceptions perpetuated in books about her over the years. Figuring out that some of that information was related to the fact that Ella had a particularly rough childhood and was a homeless teenager for a time was something I felt important to disclose to young readers even though there had been historical attempts to keep this under wraps. Ella’s past speaks directly to the type of strong, tenacious woman she was and illustrates for kids that she was able to overcome adversity and follow her dreams to success. This kind of information gets us closer to our subjects; closer to the truth of who they really were. And isn’t that the point?

At other times in my research, I have uncovered what I like to call “American heroes behaving badly.” Uh-oh. What’s a writer to do? Tarnish the reputation of a well-known figure? Maybe. Gloss over it and fail to bring it to the reader’s attention? Ignore it and hope it goes away? Of course not. But to tread here, one must do so attentively. With thought and care. I feel I have a duty to my young readers to tell them the truth about the world as I see it. Of course, my way of seeing it is as unique to me as yours is to you. But that’s all any of us have to work with. That, and integrity and ethics. If I tell readers the truth as I see it, and give them as much context as I can so that they can see things for themselves as well, all the while staying as true and honest as I possibly can, I have done my job. This was my goal in my forthcoming book Almost Astronauts: 13 Women Who Dared to Dream, which is about the 13 courageous women in 1961 who excelled at astronaut testing and continued to push onward even when NASA did not let them into the space program.

I can tell you right now that you will read about a few beloved American heroes behaving badly in this particular episode of history. But I can also assure you that, in addition to my deep personal feelings about this story, I have been fair and honest. I have taken multiple perspectives into account. Including my own.

Some may say that nonfiction should stick only to the facts, but I disagree. The kind of nonfiction I most enjoy reading, and that I believe young readers get the most out of, is the kind of nonfiction that is as alive as the people whose stories are being told. That’s what makes history exciting and that’s what gets kids excited about reading.

The topic our NCTE (National Council for Teachers of English) panel will be discussing is how we, as nonfiction writers, remain a reliable source of information while sharing our passion and point of view on a topic with young readers. It’s a very good question and one that I, like my fellow panelists—Marc Aronson, Elizabeth Partridge, and Tonya Bolden—and other nonfiction writers spend a great deal of time thinking about and incorporating when we transfer our thoughts to the page.

There are many factors that come into play, especially when writing for an audience that is older than the picture book crowd. When I delve into a topic I try to learn as much as humanly possible on a subject. This means that I sometimes uncover issues that not be entirely positive or may be difficult to address with kids. But it certainly doesn’t mean that I avoid those issues. For example, while researching Ella Fitzgerald for my Up Close: Ella Fitzgerald book, I discovered that there were many half-truths or misperceptions perpetuated in books about her over the years. Figuring out that some of that information was related to the fact that Ella had a particularly rough childhood and was a homeless teenager for a time was something I felt important to disclose to young readers even though there had been historical attempts to keep this under wraps. Ella’s past speaks directly to the type of strong, tenacious woman she was and illustrates for kids that she was able to overcome adversity and follow her dreams to success. This kind of information gets us closer to our subjects; closer to the truth of who they really were. And isn’t that the point?

At other times in my research, I have uncovered what I like to call “American heroes behaving badly.” Uh-oh. What’s a writer to do? Tarnish the reputation of a well-known figure? Maybe. Gloss over it and fail to bring it to the reader’s attention? Ignore it and hope it goes away? Of course not. But to tread here, one must do so attentively. With thought and care. I feel I have a duty to my young readers to tell them the truth about the world as I see it. Of course, my way of seeing it is as unique to me as yours is to you. But that’s all any of us have to work with. That, and integrity and ethics. If I tell readers the truth as I see it, and give them as much context as I can so that they can see things for themselves as well, all the while staying as true and honest as I possibly can, I have done my job. This was my goal in my forthcoming book Almost Astronauts: 13 Women Who Dared to Dream, which is about the 13 courageous women in 1961 who excelled at astronaut testing and continued to push onward even when NASA did not let them into the space program.

I can tell you right now that you will read about a few beloved American heroes behaving badly in this particular episode of history. But I can also assure you that, in addition to my deep personal feelings about this story, I have been fair and honest. I have taken multiple perspectives into account. Including my own.

Some may say that nonfiction should stick only to the facts, but I disagree. The kind of nonfiction I most enjoy reading, and that I believe young readers get the most out of, is the kind of nonfiction that is as alive as the people whose stories are being told. That’s what makes history exciting and that’s what gets kids excited about reading.

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Crazy About Similes!

My fall book tells a tale using only similes as the text. The easiest way to get a sense of it is to watch this video preview. The impetus to create Crazy Like Fox: A Simile Story was to follow up on a previous book of sayings (There’s a Frog in My Throat) while using a different format. Frog is a compendium of over 400 sayings; Crazy tells a story as well as having several similes on each page. Every time a character is compared to something, he or she turns into it. For example, when Rufus is sleeping like a log, on the next page he becomes a log (and even snores like a chain saw.) This enabled me to have tons of fun with the illustrations. It’s been well-received, with a starred review from Kirkus.

My fall book tells a tale using only similes as the text. The easiest way to get a sense of it is to watch this video preview. The impetus to create Crazy Like Fox: A Simile Story was to follow up on a previous book of sayings (There’s a Frog in My Throat) while using a different format. Frog is a compendium of over 400 sayings; Crazy tells a story as well as having several similes on each page. Every time a character is compared to something, he or she turns into it. For example, when Rufus is sleeping like a log, on the next page he becomes a log (and even snores like a chain saw.) This enabled me to have tons of fun with the illustrations. It’s been well-received, with a starred review from Kirkus.I’m not aware of any similar book where the text consists of only similes, but please let me know if there is one for curiosity’s sake. The title was the first simile chosen, and the plot needed to explain what “crazy like a fox” means. So, Rufus the fox had to act weird for some reason that would make sense by the end of the story. In the manuscript’s early stages, he was jumping as high as a kite to get over a fence, running as fast as the wind to escape some critter, and finally building a contraption to vault him across a river to get breakfast at Mama Somebody's Cafe. The ending seemed a tad flat, though.

Meanwhile, I was busy collecting similes. If there’s some master web site full of zillions of ‘em, I never found it. This one has a fair number (you have to scroll down a bit.) But mostly, I had to compile a list using various general idiom or cliché sites. One of my favorites is this one that you can search by key word. Of course, only a small percentage of any group of sayings are similes, so it took awhile to get a reasonable number to “audition” as part of a potential text. After amassing quite a few, for the sake of organization they had to be put in alphabetical order by first key word. Thus, as tall as a giraffe came before as tough as nails. For Frog I had made a database, but for this project a list worked fine. I did separate “like” from “as“ similes to make it easier and to ensure there was a good balance of both forms in the book. Also, I left out similes that were obviously unsuitable because they were too antiquated (as mad as a hatter), inappropriate for young children (like a bat out of hell), or probably wouldn’t fit into the story. Whatever the story turned out to be, that is.

Eventually the idea popped into my head for Rufus to pick on his friend Babette the sheep, and thus lure her into chasing him all the way to her own surprise birthday party. The party is as noisy as a herd of elephants, so of course the guests turn into... elephants! If you’ve never seen a possum, a crow, a ladybug and several other critters transformed into long-trunked proboscideans, this is your chance.

In the book biz, snags can crop up anywhere, and towards the end there was suddenly a title problem. Namely, the publisher wanted me to jettison the title Crazy Like a Fox and call it Simply Similes. Rather than freaking out (my first impulse,) I sent them a list of the pros of keeping the title as it was, plus the requirements for any alternate title (has to be catchy and fun, inspire kids to read it, tie in with the story, and so on.) I also had the chance to mention the issue to a group of teachers who all were in favor of the original title, and POOF! that little issue went away (yay!)

Monday, November 17, 2008

Horn Tooting

My newest titles were published this Fall.

All Stations! Distress! about the Titanic and Let It Begin Here! about the Battle of Lexington and Concord are departures from my usual biographical-picture-books-for-younger-readers fare. Instead, they are longer format books aimed squarely at nine to twelve-year-old readers.

Whereas my picture books are studies in “reduction” – What can I leave out without damaging the narrative arc of the story or, worse, skewing historical accuracy – The longer text in the new books allowed me to explore details of the story as well as employ more complex sentences. (Even so, I’m still a sucker for the straight-forward declarative sentence.) And I could indulge in art more appropriate for an older audience, specifically of the ‘blood and guts’ variety.

All Stations! Distress! received starred reviews from the Horn Book and School Library Journal. SLJ also awarded Let It Begin Here! a starred review.

All Stations! Distress! about the Titanic and Let It Begin Here! about the Battle of Lexington and Concord are departures from my usual biographical-picture-books-for-younger-readers fare. Instead, they are longer format books aimed squarely at nine to twelve-year-old readers.

Whereas my picture books are studies in “reduction” – What can I leave out without damaging the narrative arc of the story or, worse, skewing historical accuracy – The longer text in the new books allowed me to explore details of the story as well as employ more complex sentences. (Even so, I’m still a sucker for the straight-forward declarative sentence.) And I could indulge in art more appropriate for an older audience, specifically of the ‘blood and guts’ variety.

All Stations! Distress! received starred reviews from the Horn Book and School Library Journal. SLJ also awarded Let It Begin Here! a starred review.

Friday, November 14, 2008

"Borrowing" Fiction to Create Nonfiction?

While working out this weekend, I watched a children's DVD about an artist that I've been researching and writing about. To get into a writing groove, I love to jump on the elliptical and watch an inspiring art video. It was a nice story about a famous painter and at the very end of the long list of credits, I read, "adapted from the O. Henry story The Last Leaf".

"Interesting," I thought. "I guess I should check out this O. Henry story."

The story about this famous artist on the DVD was exactly the story, The Last Leaf. So, to understand this correctly, if showed this DVD to an art appreciation class, I'd have to say, "Well, this is a story about ______ but it's not true. The artist and other characters in the story actually knew each other, but what happens in the story never happened. They borrowed it from a fictional short story from another author."

Now, I'm all for great stories about artists that illustrate for children the power of art. I'm all for using literary techniques to help creatively tell the story; i.e. complication/resolution, flashback, foreshadowing, and pace. But, is it just me? I felt misled by the use of another author's fictional story. I believed the story to be true. It wasn't until I read the credit at the end of the credits that I learned that the story was untrue (by the way, there was no mention on the cover or the beginning credits... only the DVD author's name, not O. Henry.)

To illustrate, suppose I write a children's book about Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Frida and Diego want to give each other Christmas gifts but they don't have any money. So (can you guess where this is going?) Frida cuts her hair to sell to buy a watch fob for Diego and Diego, in turn, sells his watch to buy a beautiful clip for Frida's hair. To be fair, I'll add some art to the book. Nice story, huh? Is it okay to then add in the fine print at the end of the book, "Adapted from The Gift of the Magi by O. Henry"? Wouldn't you assume that the story actually transpired between Frida and Diego? I mean, they probably did buy each other Christmas gifts. Right?*

To give credit to the DVD, it was a nice reminder of the the power of art and it had cool computer graphics. I've purposely not mentioned the title so that someday it might not come back and bite me. And, sorry, if any other of my INKmates have "borrowed" from other famous works of fiction to tell a nonfiction story. Heck, maybe there are some award-winners that I'm not aware of that are "adapted" from other works of fiction. I don't mean to offend. It is my hope that other sage nonfiction writers would weigh in on this topic.

Anna rant is over. Please leave a nice, constructive comment.

*Ha! As I reread this, way, way back in my mind, I vaguely remember that Frida and Diego never exchanged gifts, but I may be wrong. I thought that was a little weird. Now, maybe, that would make an interesting story?

"Interesting," I thought. "I guess I should check out this O. Henry story."

The story about this famous artist on the DVD was exactly the story, The Last Leaf. So, to understand this correctly, if showed this DVD to an art appreciation class, I'd have to say, "Well, this is a story about ______ but it's not true. The artist and other characters in the story actually knew each other, but what happens in the story never happened. They borrowed it from a fictional short story from another author."

Now, I'm all for great stories about artists that illustrate for children the power of art. I'm all for using literary techniques to help creatively tell the story; i.e. complication/resolution, flashback, foreshadowing, and pace. But, is it just me? I felt misled by the use of another author's fictional story. I believed the story to be true. It wasn't until I read the credit at the end of the credits that I learned that the story was untrue (by the way, there was no mention on the cover or the beginning credits... only the DVD author's name, not O. Henry.)

To illustrate, suppose I write a children's book about Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Frida and Diego want to give each other Christmas gifts but they don't have any money. So (can you guess where this is going?) Frida cuts her hair to sell to buy a watch fob for Diego and Diego, in turn, sells his watch to buy a beautiful clip for Frida's hair. To be fair, I'll add some art to the book. Nice story, huh? Is it okay to then add in the fine print at the end of the book, "Adapted from The Gift of the Magi by O. Henry"? Wouldn't you assume that the story actually transpired between Frida and Diego? I mean, they probably did buy each other Christmas gifts. Right?*

To give credit to the DVD, it was a nice reminder of the the power of art and it had cool computer graphics. I've purposely not mentioned the title so that someday it might not come back and bite me. And, sorry, if any other of my INKmates have "borrowed" from other famous works of fiction to tell a nonfiction story. Heck, maybe there are some award-winners that I'm not aware of that are "adapted" from other works of fiction. I don't mean to offend. It is my hope that other sage nonfiction writers would weigh in on this topic.

Anna rant is over. Please leave a nice, constructive comment.

*Ha! As I reread this, way, way back in my mind, I vaguely remember that Frida and Diego never exchanged gifts, but I may be wrong. I thought that was a little weird. Now, maybe, that would make an interesting story?

Thursday, November 13, 2008

The Truth and Nothing But

I thought I was going to write this blog at a leisurely pace on an entirely different topic. Then again, after a lifetime of being called for jury duty and never being picked, I also thought I would had plenty of time to write it.

On the way home from court, it occurred to me that being a juror is a lot like researching a nonfiction book. You never come upon the important information in a neat package. You have to ingest the pieces of evidence as they come, then sort through them to create a narrative you believe best resembles the truth. Some witnesses seem to be lying to support their agendas. Others seem untrustworthy for a more benign reason. You wonder if their emotions have pushed their sense of what happened into a posture that actually feels true to them. You find both types of when you research books too. Try to figure out what was going on in Salem during the witch hunts. Or explain McCarthyism. Or many of the American myths from George and his cherry tree onward.

Sorry, this blog is going to be short. Frankly, I want to watch some bad TV, go to sleep, and get ready for tomorrow’s closing arguments and deliberations. Coming up with a verdict in this case will require much thought and hard work. I’m not going to equate being intellectually lazy in the jury room with writing a mediocre book—someone’s freedom is at stake here. But doing the best you can at both jobs may have lasting effects (albeit it, quite different ones) on the lives of people you don’t really know.

On the way home from court, it occurred to me that being a juror is a lot like researching a nonfiction book. You never come upon the important information in a neat package. You have to ingest the pieces of evidence as they come, then sort through them to create a narrative you believe best resembles the truth. Some witnesses seem to be lying to support their agendas. Others seem untrustworthy for a more benign reason. You wonder if their emotions have pushed their sense of what happened into a posture that actually feels true to them. You find both types of when you research books too. Try to figure out what was going on in Salem during the witch hunts. Or explain McCarthyism. Or many of the American myths from George and his cherry tree onward.

Sorry, this blog is going to be short. Frankly, I want to watch some bad TV, go to sleep, and get ready for tomorrow’s closing arguments and deliberations. Coming up with a verdict in this case will require much thought and hard work. I’m not going to equate being intellectually lazy in the jury room with writing a mediocre book—someone’s freedom is at stake here. But doing the best you can at both jobs may have lasting effects (albeit it, quite different ones) on the lives of people you don’t really know.

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

The Importance of Being Wrong

Here’s a diagram explaining the scientific method in simple terms - I hope whoever owns it doesn’t mind me copying it off the internet. It’s important to define the scientific method, and this diagram does a pretty good job of showing how a scientist might try to answer a specific question. What gets missed in this kind of definition is the way science progresses as much through error as trial. Accepted scientific theories are under constant attack — sometimes, as in the case of evolution, by non-scientists or scientists with agendas that trump their scientific integrity — but more significantly and more typically by other scientists working in related fields. A popular misunderstanding of this dynamic is one of the things that has led to widespread confusion about what a ‘theory’ is, whether or not science is a ‘belief system’ (I suppose it is, but not in the sense that is normally implied by the phrase).

Here’s a diagram explaining the scientific method in simple terms - I hope whoever owns it doesn’t mind me copying it off the internet. It’s important to define the scientific method, and this diagram does a pretty good job of showing how a scientist might try to answer a specific question. What gets missed in this kind of definition is the way science progresses as much through error as trial. Accepted scientific theories are under constant attack — sometimes, as in the case of evolution, by non-scientists or scientists with agendas that trump their scientific integrity — but more significantly and more typically by other scientists working in related fields. A popular misunderstanding of this dynamic is one of the things that has led to widespread confusion about what a ‘theory’ is, whether or not science is a ‘belief system’ (I suppose it is, but not in the sense that is normally implied by the phrase).One of the interesting things about having lived for a while (50+ years, in my case) is that one begins to see changes in cultural values and knowledge that might not be perceptible over a short time span. Here are a few interesting examples:

If you unplug the cable from a TV and tune it to no station, part of the snow you see on the screen is caused by radiation left over from the big bang, the moment when all the matter and energy in the universe came into being , some14 billion years ago.

If you unplug the cable from a TV and tune it to no station, part of the snow you see on the screen is caused by radiation left over from the big bang, the moment when all the matter and energy in the universe came into being , some14 billion years ago. There is a supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, equivalent in mass to about 3 1/2 million suns. Our sun rotates on its axis about once a month — this black rotates every 11 minutes. We can’t see it, because its gravitational field is so strong that light can’t escape. We know it’s there because of radio waves emitted by superheated matter as it is sucked into the black hole.

There is a supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, equivalent in mass to about 3 1/2 million suns. Our sun rotates on its axis about once a month — this black rotates every 11 minutes. We can’t see it, because its gravitational field is so strong that light can’t escape. We know it’s there because of radio waves emitted by superheated matter as it is sucked into the black hole. To the best of our knowledge, only 4% of the universe is composed of matter and energy as we experience them. Some 22% seems to be comprised of dark matter. The remaining 74% is dark energy. The best we can say about dark energy is that it is a hypothetical force that we don’t understand.

To the best of our knowledge, only 4% of the universe is composed of matter and energy as we experience them. Some 22% seems to be comprised of dark matter. The remaining 74% is dark energy. The best we can say about dark energy is that it is a hypothetical force that we don’t understand. Iridium is an element that is found in relatively high concentrations in some asteroids. In many parts of the world, we’ve found a thin layer of iridium in strata that was laid down 65 million years ago. This layer shows that an asteroid, estimated to be about ten kilometers in diameter, hit the earth with incredible force, causing a worldwide fire storm and sending up clouds of debris that may have been partly or largely responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Iridium is an element that is found in relatively high concentrations in some asteroids. In many parts of the world, we’ve found a thin layer of iridium in strata that was laid down 65 million years ago. This layer shows that an asteroid, estimated to be about ten kilometers in diameter, hit the earth with incredible force, causing a worldwide fire storm and sending up clouds of debris that may have been partly or largely responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs. 55 million years ago the Indian subcontinent, moving north on the Indian continental plate, rammed into Asia. It’s still moving north at a rate of four inches a year. The crash has created the Himalayan mountains, which are still rising at a rate of almost one foot every 100 years.

55 million years ago the Indian subcontinent, moving north on the Indian continental plate, rammed into Asia. It’s still moving north at a rate of four inches a year. The crash has created the Himalayan mountains, which are still rising at a rate of almost one foot every 100 years. Something related to the movement of the earth’s crust is the existence of superheated geothermal vents, sometimes called black smokers, on the sea floor. There, living in water than may be hundreds of degrees Fahrenheit, is an entire ecosystem based on sulfur-loving bacteria, completely independent of solar energy.

Something related to the movement of the earth’s crust is the existence of superheated geothermal vents, sometimes called black smokers, on the sea floor. There, living in water than may be hundreds of degrees Fahrenheit, is an entire ecosystem based on sulfur-loving bacteria, completely independent of solar energy. Life is digital. Four letters, AGCT, encode our genome as a sequence of some three billion base pairs on strands of DNA. It would be possible to convert this sequence to 0’s and 1’s, put it on a disk, and at some point in the future, when the technology becomes available, use it create a genetically identical individual.

Life is digital. Four letters, AGCT, encode our genome as a sequence of some three billion base pairs on strands of DNA. It would be possible to convert this sequence to 0’s and 1’s, put it on a disk, and at some point in the future, when the technology becomes available, use it create a genetically identical individual.Each of these seven examples illustrates a theory that has been generally accepted only within my lifetime. Each displaced a previously accepted view, one with many adherents that surely represented the life’s work of many scientists. The process was sometimes painful and confrontational. But when enough evidence accumulated, a new explanation was accepted. Science progresses, in large part, by being wrong. This makes science flexible and allows it to adapt to new information, and it’s the essential difference between science and other systems that try to explain why the world is the way it is.

Monday, November 10, 2008

Thankful for a President Who Reads

Trying to surf a holiday wave, I was all set to post reviews of new Thanksgiving-themed books. But they're not really thrilling me. And I only review books I’m genuinely excited about.

Plus, am I the only one who hasn’t been able to concentrate on real work ever since Obama won? Although I was inspired by, um, his rival for the nomination, I’ll admit to being among those weeping for joy on Tuesday night.

Among all his other assets, this is someone to whom words matter. Look at what he reads. Thick meaty books…Twain and Steinbeck, Graham Greene and Robert Penn Warren…lots of nonfiction… even the book I’m always trying to get my book club to pick-- Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. Some enterprising souls are recommending even more books before he takes office. But I'm too thankful to give advice. Well, maybe he might make a general proclamation someday when he's not too busy solving all the other problems: “American kids should be reading more nonfiction." But this Thanksgiving I say ask not what Obama can do for you, ask what you can do for Obama.

Plus, am I the only one who hasn’t been able to concentrate on real work ever since Obama won? Although I was inspired by, um, his rival for the nomination, I’ll admit to being among those weeping for joy on Tuesday night.

Among all his other assets, this is someone to whom words matter. Look at what he reads. Thick meaty books…Twain and Steinbeck, Graham Greene and Robert Penn Warren…lots of nonfiction… even the book I’m always trying to get my book club to pick-- Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. Some enterprising souls are recommending even more books before he takes office. But I'm too thankful to give advice. Well, maybe he might make a general proclamation someday when he's not too busy solving all the other problems: “American kids should be reading more nonfiction." But this Thanksgiving I say ask not what Obama can do for you, ask what you can do for Obama.

Friday, November 7, 2008

Getting Organized

A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of meeting Randi Miller, the only female U.S. wrestler to win a medal at the 2008 Summer Olympics. Randi is considering writing a book about her experiences as a woman who’s succeeding in a traditionally male sport, and she asked me for tips on how to get organized. As I e-mailed her my thoughts, it struck me that getting organized might also be an appropriate topic for this blog.

Organization is really important when I write. I do a lot of library research, and before I start writing, I make folders dedicated to different aspects of the story. One example: for the biography I just finished about journalist Nellie Bly, the folders included: About Nellie, Nellie’s Writing, Other Articles, Quotes (Nellie's), Back Matter, Possible Photos, and Memos and Correspondence (mine, about the book). I organize my research by putting everything that I have into the appropriate folders so as I write, I have all the notes and photocopies where I can find them. I keep the folders in a vertical file on the floor next to my desk, within arm's length of my computer keyboard.

I go through this research several times, including once to try and come up with an outline for the book. Will it be chronological or thematic? How will each chapter flow into the other? For a biography, the decision to approach the story chronologically is almost automatic. For my book on women’s sports history, Winning Ways, I originally planned to focus on themes until my editor convinced me otherwise. In the end, I used chronological chapters, but I made sure to touch on ongoing themes such as the media’s reaction to women in sports in different eras and the evolution of the clothes and equipment available to female athletes.

No matter what I plan to write, doing an outline helps. After it’s finished, I sometimes have to make adjustments in my file folders to better match the chapters of the book. I also figure out what additional research I need to do. I may want to interview experts on my topic, and I'll probably need to do more library research. These days, the Internet is an increasingly important research tool. Just last week, I learned that my weekend subscription to the New York Times makes me eligible to download up to 100 articles each month from the paper’s 157-year archive—-for FREE. What an invaluable resource for someone who writes about U.S. history! (If you don’t have a subscription, you can still download articles at a rate of one for $3.95 or 10 for $15.95.)

When any additional research is done, I start writing. Each time I come to a new chapter, I look through its folder and list topics or anecdotes I want to include. I check these off after I write them into the narrative. Sometimes I forget to include one. If that happens, I have to determine if it really needs to be in that chapter, if it can go somewhere else, or if it's not necessary at all. Another alternative is to set aside the anecdote to use in a caption. This process continues until I've written the whole book.

Occasionally, I’ll take an initial stab at a book topic by writing an article on some aspect of it. I did that several times with the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League before starting on my book, A Whole New Ball Game. I wrote about the league for Scholastic Search magazine (an article on how World War II led to its formation), for Scholastic MATH Magazine (an article on women's versus men's batting averages), and for the Sunday magazine of the California Daily News (profiles of several California players). It’s an excellent way to delve into a subject without having to plan out an entire book, and the freelance fees help pay some bills along the way.

Organization is really important when I write. I do a lot of library research, and before I start writing, I make folders dedicated to different aspects of the story. One example: for the biography I just finished about journalist Nellie Bly, the folders included: About Nellie, Nellie’s Writing, Other Articles, Quotes (Nellie's), Back Matter, Possible Photos, and Memos and Correspondence (mine, about the book). I organize my research by putting everything that I have into the appropriate folders so as I write, I have all the notes and photocopies where I can find them. I keep the folders in a vertical file on the floor next to my desk, within arm's length of my computer keyboard.

I go through this research several times, including once to try and come up with an outline for the book. Will it be chronological or thematic? How will each chapter flow into the other? For a biography, the decision to approach the story chronologically is almost automatic. For my book on women’s sports history, Winning Ways, I originally planned to focus on themes until my editor convinced me otherwise. In the end, I used chronological chapters, but I made sure to touch on ongoing themes such as the media’s reaction to women in sports in different eras and the evolution of the clothes and equipment available to female athletes.

No matter what I plan to write, doing an outline helps. After it’s finished, I sometimes have to make adjustments in my file folders to better match the chapters of the book. I also figure out what additional research I need to do. I may want to interview experts on my topic, and I'll probably need to do more library research. These days, the Internet is an increasingly important research tool. Just last week, I learned that my weekend subscription to the New York Times makes me eligible to download up to 100 articles each month from the paper’s 157-year archive—-for FREE. What an invaluable resource for someone who writes about U.S. history! (If you don’t have a subscription, you can still download articles at a rate of one for $3.95 or 10 for $15.95.)

When any additional research is done, I start writing. Each time I come to a new chapter, I look through its folder and list topics or anecdotes I want to include. I check these off after I write them into the narrative. Sometimes I forget to include one. If that happens, I have to determine if it really needs to be in that chapter, if it can go somewhere else, or if it's not necessary at all. Another alternative is to set aside the anecdote to use in a caption. This process continues until I've written the whole book.

Occasionally, I’ll take an initial stab at a book topic by writing an article on some aspect of it. I did that several times with the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League before starting on my book, A Whole New Ball Game. I wrote about the league for Scholastic Search magazine (an article on how World War II led to its formation), for Scholastic MATH Magazine (an article on women's versus men's batting averages), and for the Sunday magazine of the California Daily News (profiles of several California players). It’s an excellent way to delve into a subject without having to plan out an entire book, and the freelance fees help pay some bills along the way.

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

A Long-Distance School Visit

In this economy, schools seem to be cutting back on extras like author visits. So I’ve decided to embark on yet another (I’ve recently taken up creating and publishing videos on my website) technological direction—video conferencing. This way I can be beamed to schools without leaving my home. I can see the kids and they can see me. It’s not like doing an assembly program for a large group and it’s not like being there in person. But it allows me to do some unique things, such as directing a collaborative project that is unique to my own work.

Although I have done video conferences from a school that equipped for them, I knew nothing of the necessary technology. I found out that you need software to connect to the protocol used by the school systems, you need a webcam and, if you’re going to do a lot of video conferencing, you need something called a static IP address, all of which costs money—about $400. So I plunged ahead and within a week I was up and running for the first video conference from my own home office.

As an experiment, I contacted a wonderful school I visited last year that is set up for and quite familiar with video conferencing. Since I’m trying to get kids to make videos of tricks from my new book We Dare You! the school librarian offered participation in the project to the after-school science club, figuring that maybe12 kids would be the right number. The next day 42 kids signed up! Since a video conference can comfortably accommodate only about 25 kids, we decided to split the group into two introductory sessions.

I gave my first video conference last week. It felt strange putting on makeup and lipstick to sit in front of my computer. The kids were far more comfortable looking at me on a screen than I was talking to them. But I could hold up and show them my video camera and say, “This is what my video camera looks like, this is what the video tape looks like.” I could explain how to shoot a video and I invited my neighbor, a network TV news director to appear with me give the kids some tips on how to shoot a video. I could email a handout to the librarian summarizing the lesson. I could watch them watching my videos on the large screen. (They laughed at my material. Very reassuring!) And most importantly, I could make personal contact with them and answer their questions directly. It’s a whole new world.

Although I have done video conferences from a school that equipped for them, I knew nothing of the necessary technology. I found out that you need software to connect to the protocol used by the school systems, you need a webcam and, if you’re going to do a lot of video conferencing, you need something called a static IP address, all of which costs money—about $400. So I plunged ahead and within a week I was up and running for the first video conference from my own home office.

As an experiment, I contacted a wonderful school I visited last year that is set up for and quite familiar with video conferencing. Since I’m trying to get kids to make videos of tricks from my new book We Dare You! the school librarian offered participation in the project to the after-school science club, figuring that maybe12 kids would be the right number. The next day 42 kids signed up! Since a video conference can comfortably accommodate only about 25 kids, we decided to split the group into two introductory sessions.

I gave my first video conference last week. It felt strange putting on makeup and lipstick to sit in front of my computer. The kids were far more comfortable looking at me on a screen than I was talking to them. But I could hold up and show them my video camera and say, “This is what my video camera looks like, this is what the video tape looks like.” I could explain how to shoot a video and I invited my neighbor, a network TV news director to appear with me give the kids some tips on how to shoot a video. I could email a handout to the librarian summarizing the lesson. I could watch them watching my videos on the large screen. (They laughed at my material. Very reassuring!) And most importantly, I could make personal contact with them and answer their questions directly. It’s a whole new world.

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

Tell Them Why

When you vote today, make sure to tell your kids why. Explain to them how you made an educated choice and why it's important for each citizen in a democracy to vote.

You might want to share a little bit of Presidential history. You can discuss which Presidents you admire and who you hope will by #44.

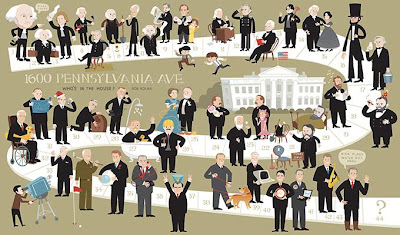

A great nonfiction book to share is OUR WHITE HOUSE. LOOKING IN, LOOKING OUT (Candlewick, 2008). Contributors include our fabulous I.N.K. bloggers Jennifer Armstrong, Don Brown, Kathleen Krull and about 105 other lovely writers.

VOTE, READ and DISCUSS. Not a bad way to spend a day.

You might want to share a little bit of Presidential history. You can discuss which Presidents you admire and who you hope will by #44.

(click to enlarge image)

OUR WHITE HOUSE. Compilation copyright © 2008 by the National Children's Book and Literacy Alliance. Illustration copyright © 2008 Bob Kolar. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

A great nonfiction book to share is OUR WHITE HOUSE. LOOKING IN, LOOKING OUT (Candlewick, 2008). Contributors include our fabulous I.N.K. bloggers Jennifer Armstrong, Don Brown, Kathleen Krull and about 105 other lovely writers.

VOTE, READ and DISCUSS. Not a bad way to spend a day.

Monday, November 3, 2008

Vote for Change, Vote for Hope -- Authors and Illustrators for Children Will

I'm too nervous and distracted to come up with anything coherent to say, so instead I'll borrow the eloquence of two great leaders.

"We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature." Abraham Lincoln, 1st Inaugural Address

"Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the promised land." Martin Luther King, Jr.

DON'T FORGET

TO VOTE ON TUESDAY

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)