Blog Posts and Lists

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

Inspiring Nonfiction Art Summer Reads for Teens

The summer of my sixteenth birthday, I brought Jane Eyre and devoured that in a day or two. Desperate to find another book to read, I wandered into my uncle’s bedroom and found the only book in English, The Agony and the Ecstasy by Irving Stone. While learning about Michelangelo’s life was interesting, what pulled me in was his passion and desire to create his art. The second I finished reading the book I hunted down a sketch pad and pencils. The remainder of my vacation was spent sketching. My brother and I hiked to the castle behind Oma’s house and I sketched from there. I sketched in Oma’s garden. At the end of that vacation, I gave Oma my sketch of Strahlenburg castle and I'll never forget her exclaims of “schon, schon, schon”, meaning “beautiful, beautiful, beautiful” in German. Oma framed that sketch and placed it in her entryway, which remained there until the day she died. That next school year is when I began art classes in high school and my love of all things art took off.

So, with summer vacation now upon us, I had to list a few wonderful nonfiction books that might ignite a passion for art in a child or student you may know. Who knows where that can lead?

Andy Warhol, Prince of Pop

by Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan

Laurel Leaf December 2007

Portrait of an Artist: A Biography of Georgia O'Keeffe

by Laurie Lisle

Washington Square Press October 1997

Delicious : The Life and Art of Wayne Thiebaud

by Susan Goldman Rubin

Chronicle Books 2007

I have listed only nonfiction YA books, though tempted to list some incredible works that are considered fiction. All Irving Stone’s books are works of fiction. For some wonderful fiction reads, check out my Goodreads page. If you have a NF YA art book to recommend, let me know and I will add it to the list.

Have to share, this year I fell in love with my new favorite book – The Swan Thieves: A Novel by Elizabeth Kostova. The Historian by Elizabeth Kostova was just recommended to my daughter by a friend so, come to think of it, The Swan Thieves would be a good YA fiction read, also.

So, if whether you are going “over the river and through the woods” or on a long plane trip or both, I hope you all have a fabulous summer vacation. And, don’t forget to take along a nonfiction book to read.

Here's to a wonderful summer vacation!

Monday, June 28, 2010

Goodbye, Mr.Gardner

A few years ago, after I finished a presentation at an elementary school in Norman, Oklahoma, a boy came up to tell me that his great grandpa also liked to make math fun. "Who's your great grandpa?" I asked. "Martin Gardner," he said.

A few years ago, after I finished a presentation at an elementary school in Norman, Oklahoma, a boy came up to tell me that his great grandpa also liked to make math fun. "Who's your great grandpa?" I asked. "Martin Gardner," he said.Martin Gardner! He might as well have told me that his great grandpa was God. No doubt about it, Martin Gardner, creator of the witty and mind-bending "Mathematical Games" column that ran for 24 years in Scientific American, could be called the God of recreational math. And Gardner was more than that. He wrote more than 70 books on subjects as diverse as philosophy, magic and literature -- The Annotated Alice, his definitive guide to Lewis Carroll's classic, was perhaps his best selling title. He was also a leading debunker of pseudoscience: after retiring from Sci Am, he sicked his penetrating logical powers on purveyors of quackery, ESP, UFOs and the like in a column called "Notes of a Fringe Watcher," published for 19 years in The Skeptical Inquirer.

Poet W.H. Auden, sci fi author Arthur C.Clarke, evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould and astronomer Carl Sagan were among his many admirers. Vladamir Nabokov named him in a novel. Astrophysicists named an asteroid after him.

Martin Gardner died last month at the age of 95. He had continued to write and publish until the last months of his life. His last article, on the pseudoscience of Oprah Winfrey, was published in March. But he will always be remembered most fondly as bringing math to millions. Of many tributes I have read, my favorite is from mathematician Ronald Graham: "He has turned thousands of children into mathematicians, and thousands of mathematicians into children."

It doesn't get any better than that.

When I read some of his obits, looking for impressive biographical material, I was surprised to find that Martin Gardner, despite his godly status, struggled to keep one step ahead of his readers. When Scientific American asked him to write a column on mathematical games, he hit the secondhand bookshops to find books about math puzzles. This became his m.o. for years as he attempted to meet his monthly deadline. "The number of puzzles I've invented you could count on your fingers," he told The New York Times.

Can you believe it? Martin Gardner, deity, scrambling to come up with the next mathematical game for his readers, and not always as original as we assumed. It reminds me of myself with this blog! Actually, it reminds me of myself with my books, and probably many other non-fiction authors with theirs. Students, teachers and librarians often seem to think we have a magical facility for turning the facts of the world into mellifluous, riveting prose, but actually we're just folks who get out there to do research, write and rewrite until we're blue in the face, and finally come up with something we're not too embarrassed to send to a waiting readership (and reviewership) -- then we hold our collective breath in the hope that someone will like it. Martin Gardner, who never took a college class in mathematics (he graduated in philosophy from the University of Chicago), wrote of the research for his Sci Am columns, "It took me so long to understand what I was writing about, that I knew how to write about it so most readers would understand it." He took complex mathematical concepts and turned them into puzzles, explaining them clearly in playful, witty, inviting ways. According to Douglas Martin's obituary in The New York Times, Gardner said his talent was asking good questions and transmitting the answers clearly and crisply.

Isn't this the talent that all non-fiction authors strive to develop? For those as successful as Martin Gardner, it expresses itself effortlessly and abundantly. The rest of us it keep plugging away at it, as if it were a Martin Gardner puzzle.

Friday, June 25, 2010

Nonfiction Authors Signing at ALA

Saturday, June 26

2:00-3:00, Marc Aronson

National Geographic Booth

2:00, Pegi Deitz Shea

Boyds Mills Press, #2952

Signing Noah Webster: Weaver of Words

Sunday, June 27

10:30-11:30, Tanya Lee Stone

Candlewick Booth #3002

Signing Almost Astronauts

11:00–12:00, Deborah Heiligman

Holt booth 2817

Signing CHARLES AND EMMA

2:30-3:30 pm, Tanya Lee Stone

Penguin Booth #2500

Signing Sandy's Circus and The Good, the Bad, and the Barbie

3:30 –4:30 pm, Deborah Heiligman

Marshall Cavendish booth 2724

Signing COOL DOG, SCHOOL DOG

Monday June 28

9:00–10:30am, Deborah Heiligman

Holt booth 2817

Signing CHARLES AND EMMA

11 am, Amy Hansen

Boyds Mills Press, #2952

Signing Bugs & Bugsicles

Thursday, June 24, 2010

Models for Nonfiction Voice

Nonfiction voice is my passion. Love experimenting with it. Love teaching about it. Love reading authors who slurp us in with compelling voice. Hester Bass does just that in her picture book, The Secret World of Walter Anderson, illustrated by E.B. Lewis and published by Candlewick.

Bass holds us with sweeping, lyrical language, and a touch of mystery.

"There once was an islander who lived in a cottage at the edge of Mississippi, where the sea meets the earth and the sky. His name was Walter Anderson. He may be the most famous American artist you've never heard of."

E.B. Lewis's art gives us the landscape from which Anderson's paintings rose.

"To see a green heron's nest, he would climb a tree. To draw a sphinx moth against a pattern of bullrushes, he would wade up to his shoulders.

Art was an adventure and Walter Anderson was an explorer, first class."

I admit a kinship with the subject. Anderson was happiest, as I am, deep in contemplation of nature. Yet I think a lot of kids will be drawn in by the curious physical details Bass brings. We learn about the mystery meals (unlabeled cans, bananas washed off ships) that Anderson ate on the island where he painted, all alone. We learn about his animal friends: the raccoons and the pigs. We imagine the discovery, after his death, of the fantastical art-covered walls in his locked room.

This is a man who chose solitude, his art, an island. It shows the beauty of nature and nature experiences, poignantly now, because his Mississippi Island is one of those being touched by the oil spill. (Although that need not enter its teaching; this book has richness and connections to many topics.)

For kids who have not had much nature contact, reading this book might be a great way to imagine this love, this world. The book would be a terrific pairing with many of the nature books by Jean Craighead George.

Another place to find some free-flowing, natural nonfiction voice is in the Read and Wonder series, also produced by Candlewick. (Most of these titles originate from Walker, the British end of their company.)

In Ice Bear, Nicola Davies folds expansive language and some culture in with her description of the polar bears' lives. Her language is expository yet the words she chooses, the lack of pronoun, and the capitalized POLAR BEAR make the creature seem like a character, as well.

"POLAR BEAR is a great hunter. It outweighs two lions and makes a tiger look small. A single paw would fill this page—and shred the paper with its claws."

I love her playfulness in another title, Big Blue Whale: "Take a look inside its mouth. Don't worry, the blue whale doesn't eat people. It doesn't even have any teeth." Her language, her perspective, is gentle and rich. It rolls along without being self conscious about form.

Although most of the titles are expository, a few dip into narrative. The Emperor's Egg, by Martin Jenkins, tells the story of the Emperor penguin father's long vigil over the egg and the hatching of the young.

Caterpillar, Caterpillar by Vivian French imparts caterpillar information through a family story about a grandfather sharing nature with his granddaughter.

Any of these books would be good models for teaching children about nonfiction nonfiction voice. Or, you could just read them for their enjoyable flow and information. (Hey, there's a concept!)

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

The Allure of Back Matter

I have a hunch that I read books differently from most people. Whether it’s fiction or nonfiction, I read the acknowledgments page first. I just love snooping into someone else’s creative process – where they did their research, whom their writing buddies are…. (I also love the directors’ commentaries on DVD movies.) Then I will look for an Author’s Note that reveals the man (or woman) behind the curtain: the author’s voice that breaks the “fourth wall.”

How I'm Doing It

Right now I’m working on author’s notes for two picture book biographies to be published in 2012. One book is a birth-to-death biography of a woman who dared to enter territory considered off-limits to women of her time. My author’s note is brief, describing how women followed her lead in the decades after her death, thanks to increased educational opportunities.

Most kids probably don’t read these ‘extras,’ but back matter is valuable for teachers and those few readers who want to learn more. These days, editors insist on bibliographies, websites, and source notes for all quotes in order to establish an author’s credibility and expertise.

How Others Do It

But many of us can’t resist going beyond the basics. We can’t bear to let go of information that doesn’t quite fit into the narrative arc of our story. M.T. Anderson’s author’s note in his quirky Strange Mr. Satie includes even more quirky details about Satie’s life and music. April Pulley Sayre’s note in Home at Last: A Song of Migration, gives us more information about each of her featured animals.

In the Old Days

Riches and More Riches

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

The Value of A Read Aloud

Read Alouds are usually fiction. Non fiction is doable albeit more difficult. Non fiction with lots of sidebars and important captions does not lend itself easily to Read Alouds. Fortunately there are plenty of other choices that work splendidly. As mentioned in a previous post, for shorter selections to finish in one day I chose Odd Boy Out by Don Brown and Eleanor by Barbara Cooney which both worked well. I watched the school librarian do a fantastic job of reading, Duel! Burr and Hamilton’s Deadly War of Words by Dennis Fradin. She used an overhead projector and read the book aloud while the children saw the pages of the book on the screen. She added details of Hamilton’s family home in a nearby town and the actual location of the duel, which she had personally visited.

The book I chose for a read aloud over a few days was Leonardo’s Horse by Jean Fritz. I think this book works well as a read aloud for several reasons. The unusual dome shape design of the book itself immediately intrigues kids. Leonard DaVinci was someone all of the fifth graders had heard of but there were plenty of interesting things yet to learn. Jean Fritz knows how to tell a good story. The mix of past and present had the kids shouting out several times, “is this true?” Oh yes.

And, I, their reader, had an extra interesting tidbit to share. When the book first came out in 2001, I took my daughter to our local bookstore for a book signing by Jean Fritz. She was wonderfully warm, attentive, and full of stories. She told us how she was lucky enough to actually attend the unveiling of the horse sculpture in Milan, Italy. The illustrator of the book, Hudson Talbott, had cleverly added her, wheelchair and all, to the cheering crowd in the illustration. My side story added just a little bit of interest to my overall rendition. And it encouraged all eyes up on the book as the kids eagerly looked for Ms. Fritz in each illustration—and happily finally found her!

It was a good reminder for me of the multifaceted nature of all good teachers, librarians, and non-fiction writers. The best of the lot are readers, writers, historians, and detectives all rolled into one. While BIC (butt in chair) is an essential mantra for all writers, non fiction writers are also faced with the glorious moral imperative of getting out into the world and learning new things. If nothing else, it makes you a better teller of tales, especially the true ones.

Monday, June 21, 2010

Summer

So, it’s the longest day of the year, here in the northern hemisphere and summer begins this morning. If you’re reading this, you may well wish to know – you probably already know that it was on this day in 1675 that Sir Christopher Wren started rebuilding St. Paul’s Cathedral, in London. There wasn’t much left of it or thousands of buildings thereabouts after that big, whacking fire that started in September of 1666. Over in Rome, only 33 years earlier (347 years ago today), that Pope Urban VIII, issued the verdict: Galileo Galilei, the Florentine, was guilty, absolutely guilty, no fooling, of not only believing, but teaching the pernicious and scandalous doctrines of the Polish astronomer, Nicolaus Copernicus. Now, Copernicus had been in his grave since the spring of 1543, but Galileo would be hanging about in the land of the living, albeit under house arrest, for another 8 ½ years before God Almighty punched the old astronomer’s ticket. And what was this ghastly theory, this notion that would undermine the foundations of the faithful, upset the cosmic apple cart? He contended that the Earth revolved around the Sun. Nothing like a new, ahead-of-its- time idea to get people all spun up into a white, frothy uproar. Why only this afternoon I was reading about Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, [I wrote about her in Rabble Rousers and Remember the Ladies. Did I ever write about Galileo? No, just a bit of factoid in the timeline in my Myles Standish book. Don’t you love knowing that Capt. Standish shared the world with Galileo? If you’re reading this, I’m betting you do.] In any case, Dr. Walker (1832-1919), was arrested more than once and she inspired all manner of outrage & ridicule for walking about in clear daylight in trousers, a.k.a. Turkish pantaloons! A “pantaloonatic,” folks called her, that and a “bloomerite.” True, this lady, the ONLY woman ever to have been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, was as neurotic as the June bugs banging into my screen door right this minute, but grateful to Mary I am and to all those pioneer “dress reformers’ every time I pull on a pair of jeans. Don’t you just love history? Happy Solstice everybody.

Friday, June 18, 2010

A Look Back: A Look Forward

I just completed a mystery for adults and sent it off to a friend to review. Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring (with Sandra Jordan, illustrations by Brian Floca) will be out in August. So I am taking a break. For the next month I will catch up on my reading.

As usual I have a stack of books next to my bed ranging from The Girl who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest and Louis Sachar’s The Card Turner to a biography of the art dealer Leo Castelli and Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s memoir Nomad. Somewhere in the mix is a novel in the voice of a dog that my friend Barbara says is a must.

I’m excited to introduce Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring, which tells the story of the collaboration between Martha Graham, Isamu Noguchi and Aaron Copland to create Martha’s most celebrated dance. Copland won a Pulitzer prize for the music. Most people don’t realize that Noguchi designed many sets for Martha’s dances over the years. Sandra and I were thinking of writing a biography of the artist. When we visited the Noguchi museum in Long island City, New York a few years ago, there was a fascinating exhibit of Noguchi’s set designs for Martha. We wondered if it would be possible to do a picture book that would capture the spirit of his work with Martha. During the years she danced, choreographed, and taught in New York, everyone referred to her as Martha. She became an icon in her own lifetime. We watched early videos of the company’s performances. It became clear that Appalachian Spring was not only the most accessible story for young readers, but it was also the most American. It takes place in the hills of Pennsylvania, where a farmer and his bride celebrate their wedding day and the completion of their new house.

The ballet debuted at the Library of Congress in 1944, when the United States was at war with Germany and Japan. Although there were intimations in the music and the dance of troubled times, the ballet ended on a hopeful note. Critics called it her valentine to Eric Hawkins, the dancer who played the husband, the man Martha eventually married. She took the role of the bride. Interestingly Merce Cunningham was the Preacher. Whenever we went to watch rehearsals of the Martha Graham Dance Company, Brian Floca was there taking photographs. Sandra and I, as I’ve written before, do an enormous amount of research for our books. I was astonished to discover that an illustrator does the same thing. More about the book in the fall. Meanwhile a happy and productive Summer to all of you.

Thursday, June 17, 2010

Will the Internet Kill Nonfiction--Continued

I was tempted to delve into a related topic in that post about the potential futures of nonfiction book publishing in concert with the Internet, but I felt that was a story for another day. When I read one of the comments from last month’s post, it was clear that day was today.

Author Marc Tyler Nobleman said, “As torchbearers for nonfiction, I feel we have a responsibility to be thinking of both books and multimedia as we create. (Film didn't kill theater. TV didn't kill radio. The Internet will not kill books; it WILL change the what and how, though.) Whether we like it or not, the world will demand it - and if we embrace it rather than resist, we can do wonderful things.”

I could not agree more. Nobleman agreed with my initial assertion that the Internet will not kill books and leapt right into the next piece of the conversation. It WILL change the what and how, yes it will. And who better to be at the forefront of the what and how but we writers of nonfiction? How exciting, in fact, to be in the game at this moment of change. The possibilities are enormous.

I can imagine Almost Astronauts, for example, in a multi-media format that would extend the reading and learning experience to dizzying depths, depending on how far the reader wants to go. We can provide new avenues and pathways of information that is integrally related to our books and each reader will have at their disposal a little or a long way to go with it, as they see fit.

It isn’t that different from the old days of getting lost in a library, traveling from book to related book in an exponentially exciting pathway of information. And it is related to the concept of hyperlinks, with a very critical difference. Hyperlinks are inserted when they are content-related, but they are still not given follow-through context. We have the ability to combine the two concepts. We can imagine different pathways for learning and set out the footlights to follow in as much depth as we wish.

This idea makes me as excited to be a reader in the future as much as a writer. I look forward to new venues for ever richer nonfiction. If anyone knows of existing examples to point out, please share!

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

Kids and the oil spill

The National Wildlife Federation web site has a page where Ranger Rick answers kids’ questions about The Big Oil Spill. For parents and teachers, another article on the site has many good tips. They include how to talk with kids of varying ages and stay as positive as possible (e.g. about how people are working hard to shut down the leak, contain the spill, clean up beaches, and help wildlife.) An excellent suggestion is to foster children’s love of nature by taking them to parks and other natural areas. The NWF has a special web site called Be Out There devoted to that goal.

Tri-State Bird Rescue & Research is in the forefront of the response on behalf of wildlife. This page shows before and after pictures of an oily pelican that was cleaned up. I can personally attest that the process works—in the early 1980s before moving to Florida, I volunteered for a short time at Tri-State which is located in Newark, Delaware. It was a little tricky hanging onto an oil-slicked goose long enough to wash it, but with plenty of hands around the washtub, we managed. There were other stories, such as having to use the bathroom while a hawk perched on the shower curtain rod above. Solution? I held a trash can lid over my head in case he felt like taking an unscheduled flight. Looking at the photograph of the current facility, it looks like they’ve come a long way since those early days.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has a multi-page story on its site about the Exxon Valdez spill in Prince William Sound that summarizes the spill, recovery efforts, and the extent of the area’s recovery. They need to update one fact on the site, though...the 1989 disaster is no longer the largest oil spill to occur in U.S. waters. Their FAQ page includes how spills spread, information about dispersants, how oil spills in rivers are different than those in the ocean, and science fair ideas on related topics.

In the coming days, what can we do to respond to this event?

Read about environmental issues

The list of winners of the Green Book Award has a variety of options from picture books to YA titles. A few titles specifically about oil spills can be found on Amazon such as Oil Spills by Peggy J. Parks (2006), Oil Spill! by Melvin Berger (1994), and Prince William by Gloria Rand (1994), about a girl who finds an oil-drenched baby seal.

Find ways to reduce your energy use

We can’t ignore the fact that we utilize petroleum directly or indirectly all day long, which is why drilling goes on in the first place. The least we can do is work to reduce our energy use.

Some relevant titles include Love Your World (DK Publishing, 2009), Why Should I Save Energy? and related titles by Jen Green (2005), and Easy to Be Green, by Ellie O’Ryan (2009). My recently released picture book The Shocking Truth about Energy has several pages of energy-saving tips towards the end of the book. Read more in this previous post.

Help those directly affected by the disaster

Tri-State Bird Rescue has many options from adopting a bird to adding a leaf to the Tree of Life in their lobby.

If possible, visit the affected Gulf Coast areas to support their tourist industry.

Last but definitely not least, don’t miss this inspiring story and video about Olivia Bouler, an 11-year-old girl who has already raised over $100,000 for conservation charities such as The Audubon Society by sending her beautiful bird drawings and paintings to people who donate. Check out her Facebook page and also Audubon’s Gulf Oil Disaster donation page.

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

It's Not all DIY: I Need Help. From Librarians.

Monday, June 14, 2010

What's Good for the Goosling...

After teaching the same course the same way for years, I’ve decided to shake it up a bit. Instead of starting with a little historical background and presenting books that embody important qualities of good nonfiction, I think I’ll begin by adapting an exercise I sometimes use when visiting elementary school classrooms. I pass out a report by Susie Goodman on brown bats that seems plagiarized from an encyclopedia. It certainly is as dull as if it had been. I tell the 4th or 5th graders we have to help Susie rewrite her report so it’s fun to read. I remind them that nonfiction can be an exciting narrative story with all the elements of fiction; you just have to make sure that they are all true.

Of course they don’t have a clue about how to do that, but I do. I simply ask them to read through this short report and tell me what they find interesting or exciting. One kid likes that bats fly at speeds up to 40 miles per hour. Another mentions echolocation. Inevitably a boy picks the part where bats use sharp teeth to chew their insect prey. I write all these things down on newsprint with space in between them.

Then we decide what feeling we want our report to evoke—happiness, humor, spookiness, whatever. Guess what they pick. Since we know from the report that these bats live all over the U.S. we can factually pick a scary location, often a cemetery or forest. That goes up on the board too, up at the top because I know (even if they don’t yet) that we’ll begin with a dramatic setting for the opening scene.

Then we continue by brainstorming about each topic—finding strong images for the dark night (nocturnal hunters), great verbs to describe diving for prey at 40 mph, and dramatic ways to describe mangling a moth (keeping in mind that this is nonfiction and there wouldn’t be enough blood to drip and splatter). Afterwards we start painting our setting and introducing our hero—a single bat looking for dinner. Slowly but surely, we draft its story of search and success with all the graphic enthusiasm a bunch of eleven-year olds can have for the macabre. We use most of the facts “Susie Goodman” copied from the World Book. And we make the most of those facts, using them as the hook that suddenly makes most anything about the brown bat come alive.

If this exercise gives young kids a new sense of nonfiction’s potential, why not MFA students? Once I have them the M.O. it will be an individual endeavor not a group one. But I’ll let them find the story in the facts—maybe about bats, maybe about the Battle of Gettysburg and its casualties of nearly 50,000 men, or the shenanigans orchids pull to get fertilized. And I'll hope that writing those few strong paragraphs will be a great hook that suddenly makes all the other nonfiction I show them come alive as well.

Friday, June 11, 2010

Deepening book content

I recently spent five days in the San Francisco Bay Area doing research for a project that excites me even more now, after this research trip, than it did before I went, because this book can easily have important personal impact on my readers.

The book will be about Audie, a courageous young dog rescued from the Michael Vick dog-fighting operation in 2007 who has found his forever family with a volunteer for Bay Area Doglovers Responsible About Pitbulls,or BAD RAP.

While learning about Audie's adjustment to a normal, loving canine existence, I realized that my book can do much more than just recount his personal saga. For example, it can help children learn that not only does training your dog in good behavior make your pet a better canine citizen, it also reinforces the bond of love and trust between you and your dog. As part of my research, I observed classes Bad Rap provides for pit bull owners and saw the joy of both humans and their dogs when they worked together towards common goals in the classes. The treats the dogs got didn't hurt, either!

I also saw how important it is for dogs in shelters to have volunteers visit to interact with them. One of the most difficult aspects of life for the rescued Vick dogs was the months they spent in shelters, with little or no human or canine interaction, before they were turned over to Bad Rap and other organizations that could put in the time needed to give them loving attention and teach them about normal life. Children want to do good as part of their communities, and helping a local animal shelter is a perfect opportunity. Children feel a natural bond with animals, and creating a project to raise money or volunteering at a shelter along with a parent or guardian can empower them to know that individuals can make a difference in the world. I'm hoping that when the book is published in Spring, 2011, my readers will not only fall in love with Audie, as I did, but will also focus some of that love into personal action.

Thursday, June 10, 2010

The Power of Books

The Week is a weekly summary of current events, with balanced reporting on how those events were covered in various print media outlets. (For any given topic, for example, you might get how it was covered by The Washington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Sacramento Bee and Slate.com.) The summaries are smart, often infused with a sense of humor, and leave me feeling like I’ve been exposed to both sides of an issue. (And how often does that happen, these days??)

The Week also provides the latest in everything from political cartoons to book reviews to theater openings. They even have a recipe each week. (I’ll admit, I’ve never actually cooked any of them, but they are fun to read.) The Health & Science page is always of particular interest to me, as it spans such a broad range of topics. In the latest issue, this page covered: the likelihood of a large earthquake in the Pacific Northwest, the sex-appeal of lowering your voice, plant-killing earthworms, the distracting effect of overhearing only one-half of a phone conversation, and the correlation between having a potbelly and getting Alzheimer’s.

And this study: the surprising effect of books in the home.

According to a 20-year study led by Mariah Evans, an associate professor of sociology and resource economics at University of Nevada, Reno, a home filled with books has a significant impact on how many years of education children will ultimately attain.

The exciting part of the study was the finding that even barely literate parents (defined as having 3 years of education) can increase the level of education their children will attain by having as few as 20 books in the home. “Even a little bit goes a long way,” Evans said. The finding offsets the commonly-held assumption that having highly-educated parents is the greatest predictor of what level of education children will attain. It turns out that parents who have a limited education can achieve similar results simply by filling their home with books.

Evans's study collected data from 27 countries, including the United States. On average, having a 500-book library in the home was just as influential as having university-educated parents—both factors increasing children’s educational levels by 3.2 years.

Few of us, to be sure, have the resources to buy and store 500 books. But anyone in America (and in many other countries) has something just as powerful: a library card.

Wednesday, June 9, 2010

Struggling with Academic Texts

I’m a strong proponent of integrating science and language arts instruction as one solution to this problem. And over the past few years, I’ve developed several strategies to help teachers do that. So you can imagine my excitement when I saw that the April 23, 2010, issue of Science included a special section called Science, Language, and Literacy.

I found most of the articles interesting, but one piece really made me think. In “Academic Language and the Challenge of Reading for Learning About Science,” Catherine E. Snow, the Patricia Albjerg Graham Professor of Education at Harvard University, is deeply concerned that today’s students are struggling to read and write academic language.

Although I feel that Snow unfairly chose a very poor writing sample to illustrate the pitfalls of using nonacademic texts to describe scientific principles, her article did raise an interesting question in my mind. Is there some characteristic inherent in academic language that makes it superior for communicating complex ideas? Or is it the act of composing a written statement, regardless of the language used, that helps scientists (or historians or people in other academic disciplines) solidify their thinking?

I’ll come back to these questions in a minute, but first I’d like to point out that Snow’s observation—that today’s students are struggling with academic language—doesn’t surprise me a bit.

After all, the nonfiction texts twenty-first century students read are farther removed from academic texts than ever before. In fact, most recent award-winning nonfiction trade books read like stories. The writing style is lively and engaging and often incorporates a variety of narrative elements. The design, format, and art in these books all work with the text to enrich the presentation.

Science textbooks are also more visually dynamic than in the past, and their writing style is less formal. Every few pages, readers encounter full-page or full-spread features that clearly show students how the science topics being discussed are relevant to their daily lives.

Today, most schools teach writing using the Six Plus One Writing Traits, which guides students in crafting prose that is interesting, easy to understand, and enjoyable to read. Six Plus One emphasizes the use of strong, active verbs and colorful phrases to grab the reader’s attention. Students are encouraged to use a conversational tone and to let their voice, or personality, infiltrate their writing. These traits are diametrically opposed to the standard conventions of academic writing, which features complex sentence structure, a distanced, authoritative tone, and judicious use of passive verbs.

When I first started reading academic texts in the 1980s, comprehending them was a challenge. The terse writing was thick with unfamiliar vocabulary and unfamiliar concepts, but the style was not all that different from the language in my high school science textbooks or the language I was expected to use when writing papers for English class.

Today’s young people have a very different experience when they encounter academic texts. For them, navigating academic writing is like translating a foreign language. Not only do they have to confront the high-level vocabulary and sophisticated concepts, they must deal with language constructions and conventions that are completely new to them.

These students have no prior experience reading or writing texts with an impersonal authoritative voice. To them, such writing seems dry, stodgy, and elitist. They have been taught to focus on specifics and provide rich details, so they find the more general approach of academic texts vague and confusing. They have learned to value writing that flows well and is easy to follow, so prose with complex grammatical constructions seems impenetrable. No wonder they are struggling.

At the end of her article, Snow recommends that educators spend more time helping students learn to process academic writing. But I wonder if that’s really the best course of action.

I worry that middle school and high school students faced with the arduous task of deciphering academic text may become so frustrated that they lose their interest in science. That’s the last thing we want to happen. Maybe it would be better if, instead, academic writing evolved to reflect the way twenty-first century learners approach the world.

Put another way, if academic writing were to become less formal and less terse, would the communication of scientific ideas suffer?

According to Rhonda J. Maxwell, author of Writing Across the Curriculum in Middle and High Schools (Allyn & Bacon, 1995), “Writing . . . helps students synthesize knowledge. When students organize their ideas through writing, the information makes more sense to them.” Based on Maxwell’s observations, I’m inclined to think that what matters is the writing process and the critical thinking it requires—not the language conventions employed by the author.

What do you think?

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Walk It Out

I do some of my best work on the streets. When my legs are moving and my lungs are filling with fresh air, words and ideas seem to flow more freely through my mind than when I’m seated in front of my computer, when the former copy editor in me questions every little word before it’s allowed to hit the screen. Those words that do make it down run the risk of being deleted within nanoseconds by this scornful critic.

But for some reason, when I’m walking the tree-lined roads of my neighborhood or the bike path by the Potomac River or even busy streets downtown—as long as I’m putting one foot in front of the other—it’s easier to cut my poor writer self a break. I turn the words and ideas and problems over and around and inside out and upside down and play with them. I dare to try crazy things, to be silly. I talk aloud a lot. If I’m working on a biography, I sometimes address my subject and ask him or her for help. By this point he or she has probably already crawled under my skin. How in the world, Professor Einstein, can I explain special relativity in a way that 10-year-olds will understand? Tell me, Annie Sullivan, how am I ever going to meet my deadline for your book if I can’t come up with a lead? I still get goose bumps when I think of the impatient voice that broke into my thoughts shortly after I asked that question. It was female, with a light Irish accent, and it upbraided me for being such a pitiful procrastinator: "Sure, if you'll stop lingering over the newspaper every morning for hours wasting time on things you don't even remember reading about later, then you'll have time to write my story. And be sure you do it well." Ouch. Annie would have reminded me about BIC, no doubt, but I think she would have also been sympathetic to my need to walk. She was a great lover of nature, and she built much of Helen’s early education around exploring the countryside together.

Monday, June 7, 2010

I.N.K. News for June

Karen Romano Young is headed for the Arctic! She's taking part in the NASA-sponsored ICESCAPE mission aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Healy, and will be at sea for two weeks in June. The Healy, an icebreaker, will carry nearly 50 scientists who are studying the effects of climate change on the Arctic Ocean and its ice. Karen will be researching a new book called Investigating the Arctic, drawing a science comic for Drawing Flies (http://www.jayhosler.com/jshblog/), creating a podcast for the Encyclopedia of Life (www.eol.org), and blogging at Science + Story. (http://scienceandstory.blogspot.com/) And her new book, Doodlebug, is in the warehouse June 8! (www.karenromanoyoung.com)

Dorothy Patent just returned from a trip to California for research on a book about one of the dogs rescued from the Michael Vick dog-fighting ring. She's fallen in love with her subject, named Audie. Look for the book is Spring, 2011.

Susanna Reich be speaking at the Metro New York SCBWI Professional Series on Tuesday, June 8. Author illustrator Melanie Hope Greenberg and I will be talking about "Marketing to the Max: Publicity for Children's Book Authors and Illustrators." http://metro.nyscbwi.org/profseries.htm

Friday, June 4, 2010

My Favorite Fan

In 1993, when my book, A Whole New Ball Game: The Story of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, came out, I sent a copy to Lou Arnold. I had met Lou, a former pitcher in the league, several years before, and she had become a friend. One day, I got home from work and found the absolutely best message ever on my answering machine. It was Lou, and she said, “Sue, I read your book and I wanted to call and tell you what a great job you did. You did us proud, Susie. Good job.”

It’s been 17 years, but I still have that message, copied from the answering machine to a digital recorder for posterity. I’ve been thinking about it a lot lately. Last week, on May 27, Lou died at age 87, after a long struggle with a whole host of health issues that would have killed a lesser person years earlier. Her passing hasn’t garnered the same media blitz that followed the death of another AAGPBL player, Dorothy Kamenshek, 10 days before. Kammie was a star—in Lou’s New England accent, that would have come out “stahh”—and she certainly deserved every bit of attention she received. But Lou, who truly was the heart of the league and who did so much to communicate its history and spirit to younger generations, also deserves a public tribute. So I’ve decided to co-opt my monthly post to tell you a little about her.

Louise “Lou” Arnold was born in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, the 13th child of George and Mary Ann (McCormick) Arnold. The number 13 meant a lot to her. She would wear it on the back of her South Bend (Indiana) Blue Sox uniform during her four years in the All-American. And number 13 did Pawtucket proud. In 1951, she helped South Bend win the league championship with a .833 winning percentage, throwing 32 consecutive scoreless innings and pitching nine complete games out of 11 starts. (Today’s major leaguers win praise if they pitch even one complete game.) She also threw a one-hitter.

South Bend was so welcoming to Lou that she decided to stay there. She worked for the Bendix Corporation for 30 years and then retired into a world that was just starting to rediscover the AAGPBL through books and Penny Marshall’s hit film, A League of Their Own. Lou quickly became a favorite of the younger generations who were inspired by the pioneer ballplayers because she opened her heart to them and seemed as impressed with their achievements as they were with hers. Even several of the actresses from Marshall’s movie became her good friends.

I got to see Lou at least once a year at the annual AAGPBL Players Association reunions, and if they were in the Midwest, we’d be sure to get out to Steak ‘n Shake, home of fantastic milkshakes and “steakburgers.” (Why, oh why, are there no Steak ‘n Shake franchises in the New York area?) Each time, Lou would have the wait staff eating out of her hand, asking for autographs and listening to her every word about her time in the league. She was a veritable pied piper of women’s baseball, the league’s unofficial ambassador of good will. People loved her and she loved them right back.

Lou had an amazing way of making you feel special. If she believed in you, you felt you could do anything. What a great fan to have as an author just starting out. What a great friend to have all these years since.

Wednesday, June 2, 2010

An Ice Place to Visit

There’s a reason I write about science. Back in the day, when I worked for Scholastic News, I wrote on every subject, researching, interviewing people, drafting, and revising. Fresh out of college, I quickly learned that the people I liked talking to the most were scientists. They were passionate, enthusiastic, and genuine in their desire to tell kids about their work and to inspire them to get into science. What’s more, their lives were a dream-come-true of adventure, exotic locations, cool skills, and gorgeous animals.

I’ve learned that this science magic extends outside the circle of scientists to the people who work with scientists to tell their stories: reporters, mappers, photographers, illustrators, and yes, writers. We’re the lucky ones who get to go along -- virtually and sometimes really -- to observe, document, nose around, loom over the shoulders of, and sometimes even help scientists as they work.

Next week I fly to the Aleutian Islands, where I’ll board the Coast Guard Cutter Healy, an icebreaking ship, for the NASA-sponsored research cruise called ICESCAPE, which means Impacts of Climate Change on the Eco-Systems and Chemistry of the Arctic Pacific Environment. For two weeks, I’ll be at the elbows of 48 scientists as they study what climate change is doing to the Arctic. My experiences will ultimately end up in a number of locations, including NASA webpages, Odyssey magazine, and a new book on the Arctic (I published Arctic Investigations in 2000, but the situation up north has changed so radically due to global warming that everything needs to be redone.)

I’m also being hosted by another science writer, Ann Downer-Hazell, on her blog Science + Story. Ann is the author of fantasy novels and nonfiction books for children, including the forthcoming Elephant Talk: The Surprising Science of Elephant Communication (Lerner, spring 2011), for which she spent quality time with two Asian elephants, learned about the lives of mahouts in Nepal, interviewed people working to reduce human contact for elephants in Africa, and visited the enshrined tail of Jumbo, the world’s most famous elephant, whose remains are treated as sacred relics by the athletes of Tufts University, which owns them.

A former editor at Harvard University Press, Ann has edited such works as Rosamond Purcell’s extraordinary Egg and Nest, and now heads Elefolio LLC, a life science communication company which develops projects in the life sciences for print and digital publishers. She hosts two blogs, Glass Salamander, about fantasy and other good reads, and Science + Story, whose stated goal is “to highlight story in science wherever it can be found, as well as to muse on the place where art and science meet.”

Among the recent topics of Science + Story you’ll find robot mice, steampunk movies, zombie animals, comics about viruses, squirrel appreciation, and jetpacks. When I mention these to Ann, asking how ICESCAPE fits in, she laughs and says, “You left out robot jellyfish!” before responding, “To me the question is following the cool.” She credits her ten-year-old son Ben for inspiring her to follow the weird as well. “I have the ten-year-old boy I deserve, which allows me to indulge my own ten-year-old vibe,” including a fondness for the paranormal, cryptozoology, mummies, monsters, Jonny Quest, secret agents, Tintin, Batman, and mad scientists. Reading about Madeleine L’Engle’s mom-scientist who cooks beef stew in the lab over a Bunsen burner in A Wrinkle in Time further reinforced the do-it-yourself ethic in science for Ann.

The blog entry in which Science + Story introduces my visit to the far north kicks off with a discussion of the book The 7 Professors of the Far North, a nod to Tintin. “This is an example of a story that creates a bridge for kids between interesting fiction and real science. I look for stories -- real and fictional -- that imbue science with adventure, discovery, and a seat-of-the-pants what-happens-next feeling.” Ann tells me, “Ben and I finished reading The 7 Professors, and within 48 hours I heard about your trip to the Arctic.”

There’s so much we don’t know about the Arctic Circle, about the Arctic Ocean, about the ocean in general. I don’t know what I’m going to find in the Arctic, how I will feel, or how it will be. Will I be able to sleep in a loud icebreaker? Will I be freezing or frightened or seasick? Will there be orca, beluga, bowhead whales, walrus, polar bears? What will 24-hour daylight be like? How will the Arctic smell and sound? What, oh what, will the scientists aboard discover? You’ll be able to follow my travels intermittently on Science + Story. Thank you, Ann!

Interactivity Is as Old as Ancient Greece

Before there were interactive video games, or choice on a computer of alternative endings to a story, or the ability to download your own play-list of songs there was a simple verbal way to invite thought and interactivity---namely, the question. Asking interesting, thought provoking questions is one of the most effective ways to educate according to Socrates, who lived almost 2500 years ago. The Socratic method of inquiry was supposed to produce critical thinking as well as alter incorrect perceptions in the pursuit of real knowledge. “Socrates once said, ‘I know you won't believe me, but the highest form of Human Excellence is to question oneself and others.’” Such questions are the basis of the law and of science as well as education.

Kids ask a lot of questions, often to the point of annoyance. What are the reasons for these questions? Sometimes it’s to get a response from an inattentive adult, sometimes it’s to verify something they already  know is true, sometimes it’s because of real curiosity. Often, in school, it’s to get an answer quickly and easily because there is a test coming up. And when this last kind of question gets the quick answer, what happens? The inquiry stops dead. That was not Socrates’ intention.

know is true, sometimes it’s because of real curiosity. Often, in school, it’s to get an answer quickly and easily because there is a test coming up. And when this last kind of question gets the quick answer, what happens? The inquiry stops dead. That was not Socrates’ intention.

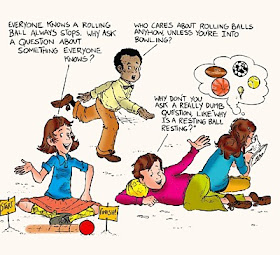

My new book, What’s the BIG Idea? Amazing Science Questions for the Curious Kid is an attempt to honor the question itself, before rushing into an answer. I explain in the introduction that a “BIG Idea” is one that has no quick or easy answer and that there are four BIG ideas in this book: motion, energy, matter and life. Science tackles big ideas. How? The same way you eat an elephant, one bite at a time and each bite is a question. Sometimes the question can seem really dumb. So each question in the book is a double page spread with an illustration of kids making editorial comments on the question. The idea is to get the reader to really think about the question before turning the page and launching into an explanation that ultimately contributes to understanding a fundamental scientific principle.

Here is the art for the first question about motion: Why does a rolling ball stop rolling?

Why is the question so important to learning? Because it gives the student time to pause, to prepare for an answer, to suggest hypotheses to him/herself. Questions even work well in speeches because they keep an audience engaged. Even if one person is doing all the talking, answering one’s own questions makes a speech more conversational—more of a two-way street. The emphasis on testing in schools today produces a culture that is too answer-oriented. There is such finality to an answer. Some answers simply discourage any further inquiry but for many people there is discomfort in not-knowing an answer. Didactic systems that provide all the answers are anti-intellectual and suppress curiosity but their comfort zone creates illusion of safety and an excuse for mental laziness. Children and scientists both enjoy “dancing with mystery.” And that's what I hope to encourage that with this book.

One last thing, I’ve made a video promoting What's the BIG Idea? and it’s located here.