Before there were interactive video games, or choice on a computer of alternative endings to a story, or the ability to download your own play-list of songs there was a simple verbal way to invite thought and interactivity---namely, the question. Asking interesting, thought provoking questions is one of the most effective ways to educate according to Socrates, who lived almost 2500 years ago. The Socratic method of inquiry was supposed to produce critical thinking as well as alter incorrect perceptions in the pursuit of real knowledge. “Socrates once said, ‘I know you won't believe me, but the highest form of Human Excellence is to question oneself and others.’” Such questions are the basis of the law and of science as well as education.

Kids ask a lot of questions, often to the point of annoyance. What are the reasons for these questions? Sometimes it’s to get a response from an inattentive adult, sometimes it’s to verify something they already  know is true, sometimes it’s because of real curiosity. Often, in school, it’s to get an answer quickly and easily because there is a test coming up. And when this last kind of question gets the quick answer, what happens? The inquiry stops dead. That was not Socrates’ intention.

know is true, sometimes it’s because of real curiosity. Often, in school, it’s to get an answer quickly and easily because there is a test coming up. And when this last kind of question gets the quick answer, what happens? The inquiry stops dead. That was not Socrates’ intention.

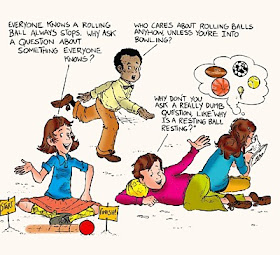

My new book, What’s the BIG Idea? Amazing Science Questions for the Curious Kid is an attempt to honor the question itself, before rushing into an answer. I explain in the introduction that a “BIG Idea” is one that has no quick or easy answer and that there are four BIG ideas in this book: motion, energy, matter and life. Science tackles big ideas. How? The same way you eat an elephant, one bite at a time and each bite is a question. Sometimes the question can seem really dumb. So each question in the book is a double page spread with an illustration of kids making editorial comments on the question. The idea is to get the reader to really think about the question before turning the page and launching into an explanation that ultimately contributes to understanding a fundamental scientific principle.

Here is the art for the first question about motion: Why does a rolling ball stop rolling?

Why is the question so important to learning? Because it gives the student time to pause, to prepare for an answer, to suggest hypotheses to him/herself. Questions even work well in speeches because they keep an audience engaged. Even if one person is doing all the talking, answering one’s own questions makes a speech more conversational—more of a two-way street. The emphasis on testing in schools today produces a culture that is too answer-oriented. There is such finality to an answer. Some answers simply discourage any further inquiry but for many people there is discomfort in not-knowing an answer. Didactic systems that provide all the answers are anti-intellectual and suppress curiosity but their comfort zone creates illusion of safety and an excuse for mental laziness. Children and scientists both enjoy “dancing with mystery.” And that's what I hope to encourage that with this book.

One last thing, I’ve made a video promoting What's the BIG Idea? and it’s located here.

Vicki,

ReplyDeleteGlad you brought up the topic "asking questions." It's a big, broad subject that is so important to us nonfiction writers.

I find coming up with a well-placed question more creative than learning the answer. In fact, I now include a section on the art of the question in school presentations. This is done interactively, using a variation of the Socratic Method. Kids love it and so do I.

Can't wait to read the book, VC. congrats!